Unravelling Some Mechanistic and Clinical Aspects of Immunological Drug-Drug Interactions

Dr Sean Hammond, as a member of an interdisciplinary team, has recently published the third of a series of papers seeking to unravel mechanistic and clinical aspects of the immunological drug-drug interactions that occur with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Immunotoxicology Lead

Sean joined ApconiX about a year ago as Immunotoxicology Lead. Working across multiple services from target safety assessments to project toxicology and late stage consultancy, Sean helps to provide insight on immunotoxicology in all stages of drug discovery and development. “As with all branches of medicine, early risk mitigation in immunology is an essential element of successful projects. Immunotoxicity is a relative newcomer compared with toxicities in other organ systems such the cardiovascular system in terms of our understanding. The recent work on immune checkpoint inhibitors has highlighted immunological drug-drug interactions as an emerging issue with a significant potential clinical impact,” commented Sean.

Honorary Lecturer

Sean completed his PhD at the University of Liverpool, following on from his first degree in Pharmacology. Continuing his association with the University of Liverpool, Sean is an Honorary Lecturer at the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at the University.

“To me, the PhD is a journey to becoming an independent scientist, and I had good fortune in completing my own PhD in the brilliant hypersensitivity group at Liverpool with Dean Naisbitt. I enjoyed learning from and working collaboratively with so many great scientists, and this work is a great example of a project benefitting from interdisciplinary expertise. As always in science, the good work continues, and I am very proud to have a continued role in it and to have maintained great working relationships with several academics.”

Sean continued, “The theoretical/conceptual challenges: reviewing literature, considering, speculating, and then formulating a pragmatic plan for evaluating the hypothesis is what has always appealed to me as a scientist. Now that I am more involved in the mentoring side with PhD students, I am even more fortunate in that I get to watch and hopefully help others embark on and negotiate this journey, which truly is something to behold.”

Here Sean explains some of the research the papers cover.

Potential Immunological Drug-Drug Interactions with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

In T-cell biology, two signals determine the specificity and the qualitative nature of a response to a target. For signal 1, the highly specific T-cell receptor recognises antigens presented on the surface of neighbouring cells to determine what the T-cell sees. But how the T-cell interprets this antigen, in terms of whether it launches a response or simply ignores the antigen, is determined by the integration of an array of co-signalling proteins that are collectively referred to as signal 2. Of these signalling proteins, some have activating qualities, whilst others (immune checkpoints) are inhibitory.

Immune checkpoints play important roles in immunological homeostasis where their role is to prevent potentially damaging runaway immune responses (such as autoimmunity) by providing “off” signals to T-cells. They have recently been brought into the spotlight in cancer, where they serve as a mechanism by which cancer can evade destruction by the immune system. Targeting immune checkpoints with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can prevent this mechanism, and as immune checkpoints have been developed, they have changed the therapeutic landscape for cancer.

Unfortunately, advancements in immuno-oncology have been accompanied by the advent and rise of novel adverse drug reactions, referred to as immune-related adverse events (irAEs). These reactions are caused by the disruption of the normal role of the immune checkpoints, (allowing those runaway immune responses to happen).

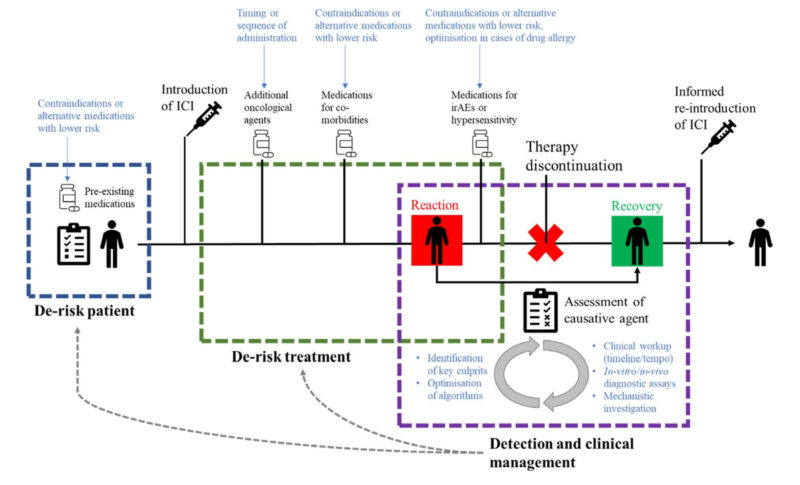

Sean added, “IrAEs are mostly the direct result of the on-target pharmacology of immune checkpoint inhibitors and are therefore often called on-target off-tissue events. Ultimately, the aim with immune oncology is to enhance the tumour-specific immune response, but we go about this by systemically blocking immune checkpoints, which means that we also enhance deleterious responses. The overall picture is therefore that we systemically deregulate immune responses in treated patients. This is challenging as it means there is little to disconnect the mechanisms of toxicity and efficacy. Whilst we hope to shunt patients into a therapeutic window where we see efficacy against the tumour without toxicity, this is seldom the case in practice, as the two are often strongly correlated.” Figure 1.

Figure 1: ICI therapy paradigm: the on-target effects of ICIs deregulate an individual’s tumour specific (efficacy) and autoreactive or otherwise deleterious (toxicity) T cells on a continuum. Respective thresholds may be set relative to each other in a given patient by the precursor tumour response and intrinsic susceptibility to autoimmune/aberrant T cell responses [2].

What has recently become apparent is that ICIs can also change how patients react to other drugs. Drug allergy/hypersensitivity is usually a rare phenomenon but there is now evidence that patients treated with ICIs are more likely to experience this type of reaction. The first two manuscripts in the series documented how ICIs have played a role in the initiation of drug allergy in patients. One investigated the increased incidence of hypersensitivity reactions observed in patients receiving concurrent ICIs and sulfasalazine. A study was carried out to characterise the T cells involved in the pathogenesis of such reactions and recapitulate the effects of inhibitory checkpoint blockade on de novo T cell priming responses to compounds within in vitro platforms derived from healthy donors [1]. What this experience showed was patients on ICIs are less likely to tolerated new drugs they are introduced to.

The second example encountered was with a patient who had been administered the radio contrast media amidotrizoate multiple times without issue but who then developed a Stevens-Johnson syndrome reaction after coadministration of atezolizumab [2]. Causality was confirmed by a positive re-challenge with amidotrizoate and laboratory investigations that implicated T cells.

Sean explained “The introduction of atezolizumab appears to have altered the immunologic response to amidotrizoate in terms of the tolerance–elicitation continuum. This was a very clear demonstration that the tolerability of drugs which patients are already on can be dramatically altered when ICIs are given to a patient. This is akin to the way ICIs are generally thought to work against cancer, through the reinvigoration of exhausted T cells. The findings of the study also highlighted the importance of considering all concomitant medications in patients on ICIs who develop immune-mediated adverse reactions (irAEs)”.

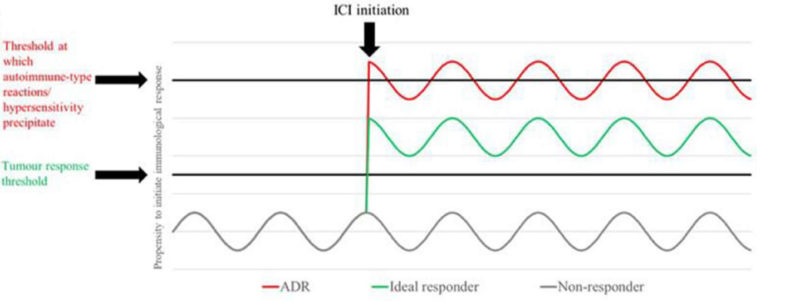

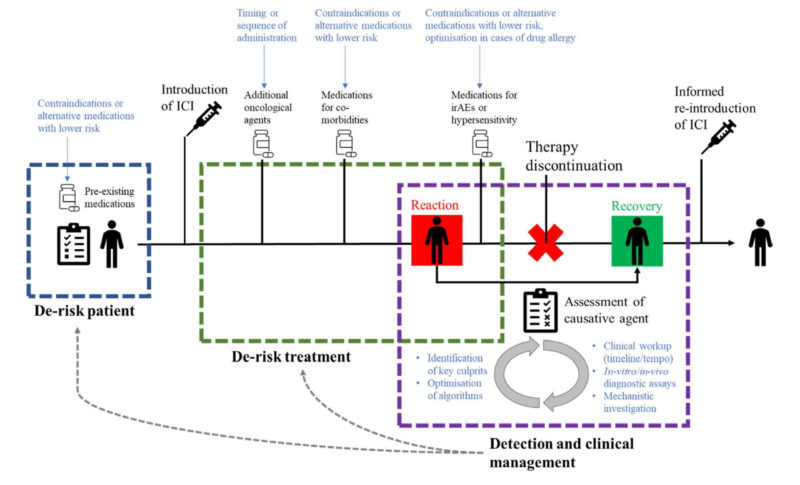

The existence of irAEs have, in themselves, caused significant challenge associated with multi-organ impact, therapeutic uncertainty and high treatment burdens alongside unpredictable incidence and impact on efficacy. With regards to the possibility that drug hypersensitivity contributes to this, understanding potential drugs of interest and the differences in management in the presence of a xenobiotic-induced hypersensitivity has the potential to modify clinical practice in an expanding number of cancer patients. This could lead to more considered therapeutic combinations within oncology and reduce the incidence of significant toxicity which is blighting the otherwise positive impact of ICI treatment [3].

Figure 2: Theoretical patient journey through pre-treatment screening, administration of ICI therapy, hypersensitivity reaction, recovery, and reinstatement of ICI treatment. Potential encounters with concomitant medications are outlined across the three key areas of intervention with suggested areas of investigation outlined in blue [3].

Sean added, “Helping clients approach and understand this very complex area is very rewarding. What is clear is that the immunotherapy landscape is continuing to grow, and so the immunological interplay between drugs is becoming more important. In the clinic, we must learn quickly, and adapt to what is in front of us in terms of what is and isn’t tolerable, what can be modified in a regimen to de-risk the therapeutic journey at various stages, and what the best course of action is when things do go awry. The reasons we must do this are twofold – firstly, no-one wants a potentially life-threatening reaction to a drug. Secondly, the patients concerned have cancer, and many irAEs necessitate discontinuation of the ICI and prompt the use of ameliorative immunosuppressive treatments, potentially to the detriment of anti-tumour efficacy. Any reactions we avoid potentially represent a safer and more efficacious therapeutic course for those patients.”

References

[1] Sean Hammond, Anna Olsson-Brown, Sophie Grice, Andrew Gibson, Joshua Gardner, Jose Luis Castrejón-Flores, Carol Jolly, Benjamin Alexis Fisher, Neil Steven, Catherine Betts, Munir Pirmohamed, Xiaoli Meng, Dean John Naisbitt, Checkpoint Inhibition Reduces the Threshold for Drug-Specific T-Cell Priming and Increases the Incidence of Sulfasalazine Hypersensitivity, Toxicological Sciences, Volume 186, Issue 1, March 2022, Pages 58–69, https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfab144

[2] Hammond S, Olsson-Brown A, Gardner J, Thomson P, Ali SE, Jolly C, Carr D, Ressel L, Pirmohamed M, Naisbitt D. T cell mediated hypersensitivity to previously tolerated iodinated contrast media precipitated by introduction of atezolizumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2021 May;9(5). (Figure unchanged from publication.) https://doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002521

[3] Hammond S, Olsson-Brown A, Grice S, Naisbitt DJ. Does immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy increase the frequency of adverse reactions to concomitant medications? Clin Exp Allergy. 2022 Mar 25. (Figure unchanged from publication.) http://doi: 10.1111/cea.14134